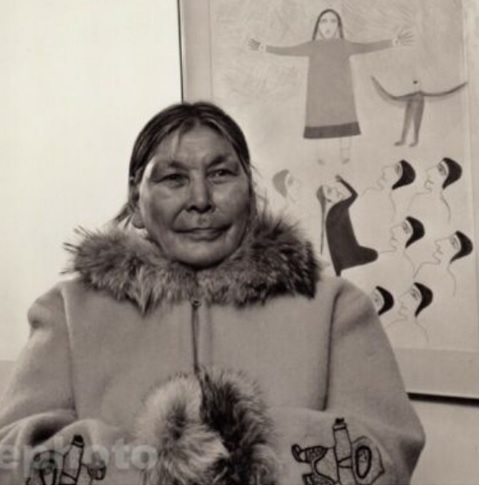

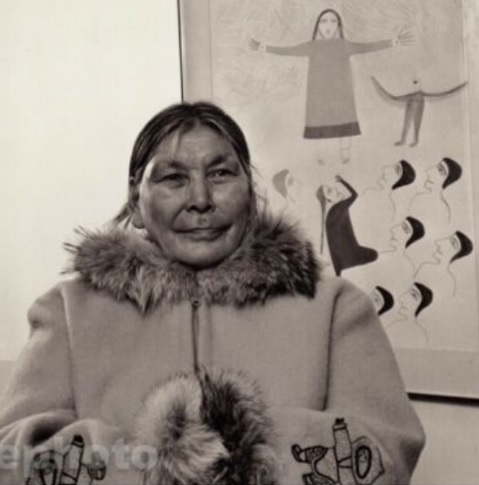

Jessie Oonark

Before her rise to fame as one of the foremost Inuit Artists in the world, Oonark lived a difficult life. She was married off at a very young age, likely in the hope her husband could better provide for her. From this marriage she bore 12 children. Her husband and four of her children died in the early 50’s, likely due to the effects of malnutrition and starvation, the result of widespread famine among the Inuit from scarcity of food resources and changing migration patterns. Jesse herself, and some of her remaining children, were on the brink of starvation death as well, when her son, William Noah, walked from their camp to the nearest town of Baker Lake to get help. Thankfully the remaining family was rescued and relocated to Baker Lake where they received the support they needed to survive. It is there that Jesse began to create drawings that would lead to her becoming the first Inuit Artist from her region to be included in the new printmaking program recently begun at Cape Dorset. Her participation in the Dorset printmaking program led to the founding of a similar program at Baker Lake in 1963. The rest is history.

As Kenojuak was to Cape Dorset, Jesse Oonark became to Baker Lake. They are each queens of their respective arctic kingdoms, and their lifetime body of work and artistic achievements made them world famous and beloved, and also brought worldwide renown to the art programs they were a part of creating. Generations of Inuit Artists have benefitted from their legacy of success, as the world of art lovers and collectors wait anxiously for new art and print releases by their favorite Inuit artists, and compete with one another to purchase rare vintage work by the artists, whose works have outlived them, when it comes up for auction from private collections. Both Jesse’s and Kenojuak’s works have recently set world records at auctions, and their legacies as master Inuit artists of the highest achievement only continue to grow.

Jesse’s further legacy is in her surviving children, who all became artists, most of whom have created their own artistic legacies of achievement. These include: William Noah, Victoria Mamnguqsualuq, Janet Kigusiuq, Mary Yuusipik, Nancy Pukingnaq, Miriam Marealik Qiyuk, and Josiah Nuilaalik.

——

“Jessie Oonark, OC RCA, was a prolific and influential Canadian Inuit artist of the Utkuhihalingmiut, whose wall hangings, prints and drawings are in major collections around the world including the National Gallery of Canada.

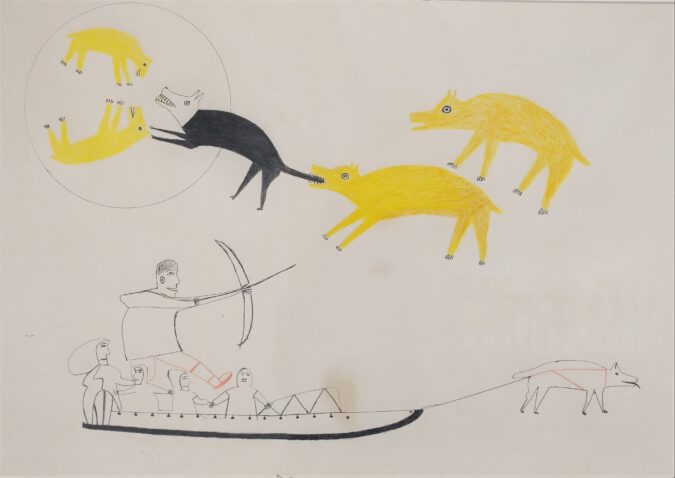

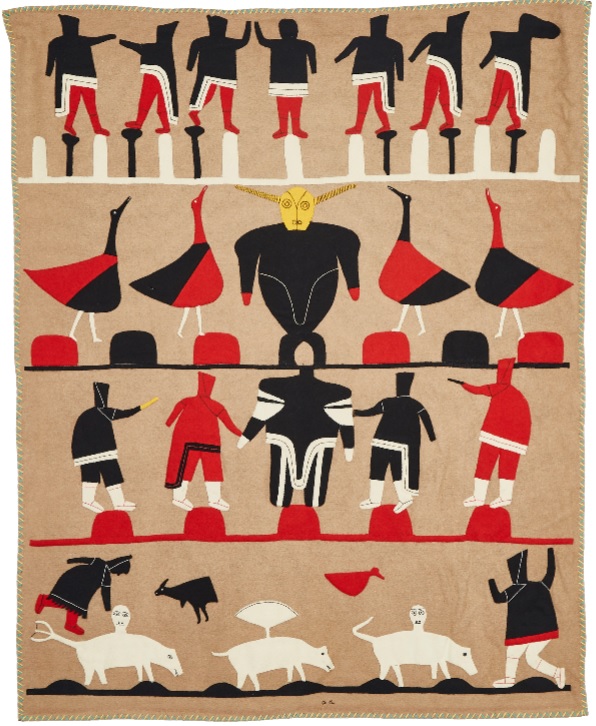

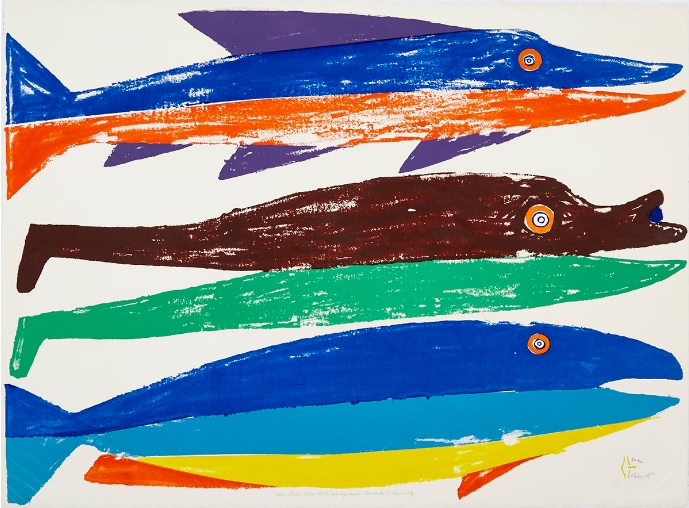

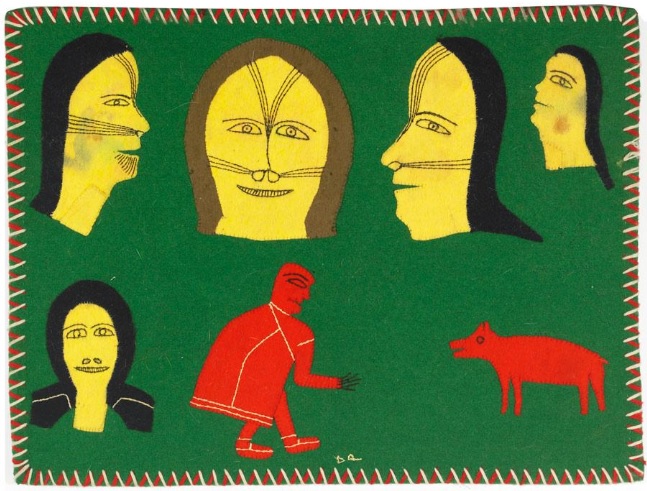

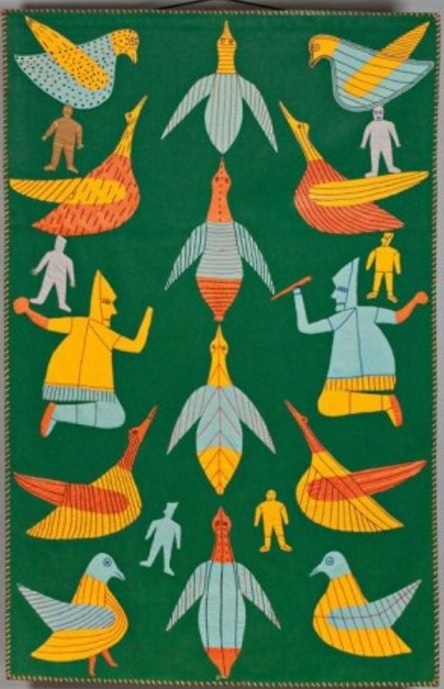

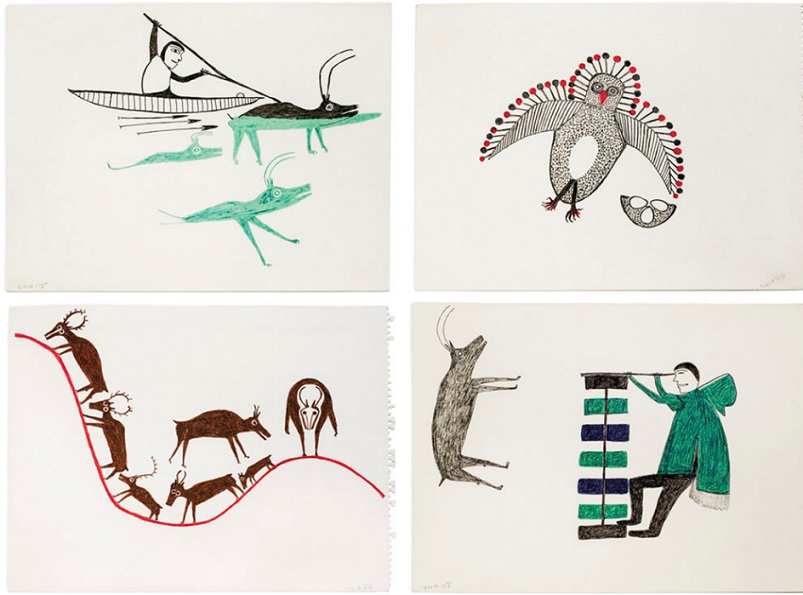

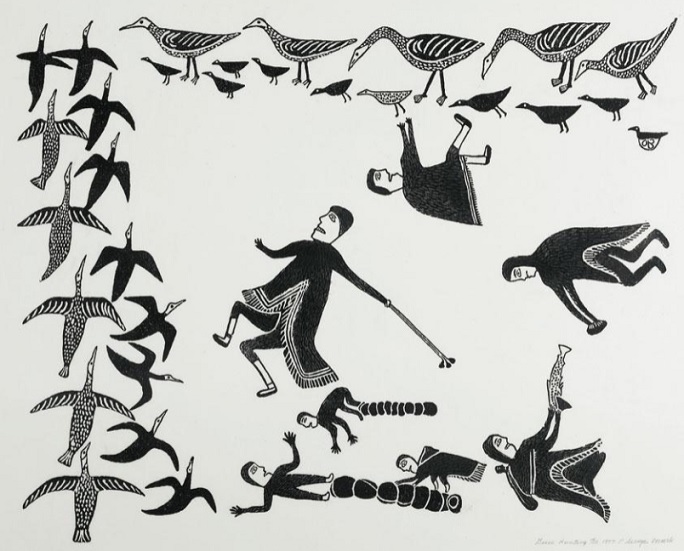

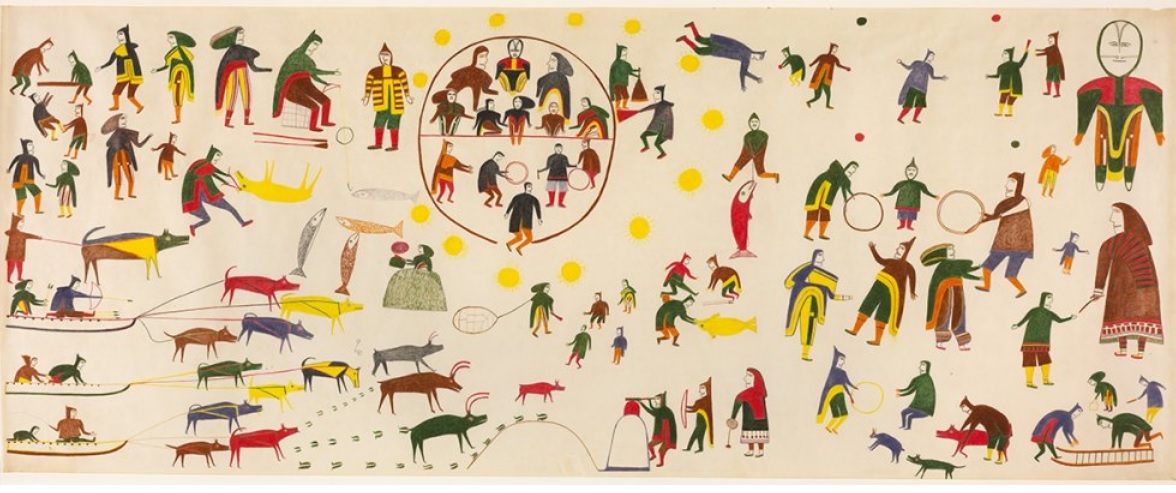

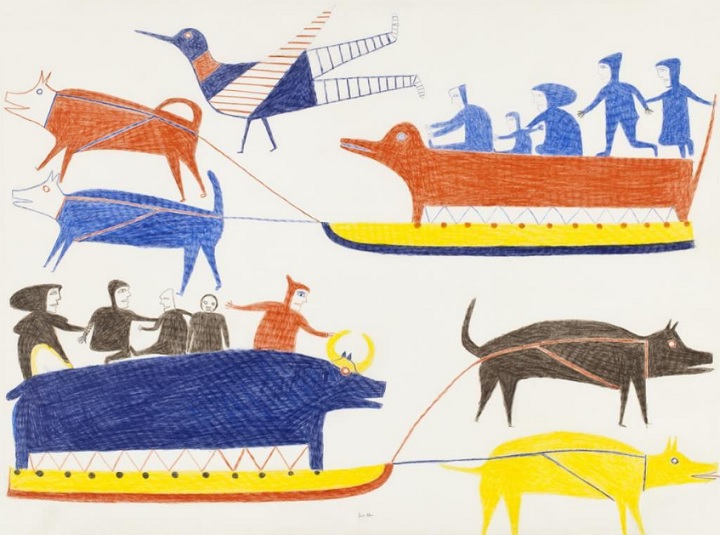

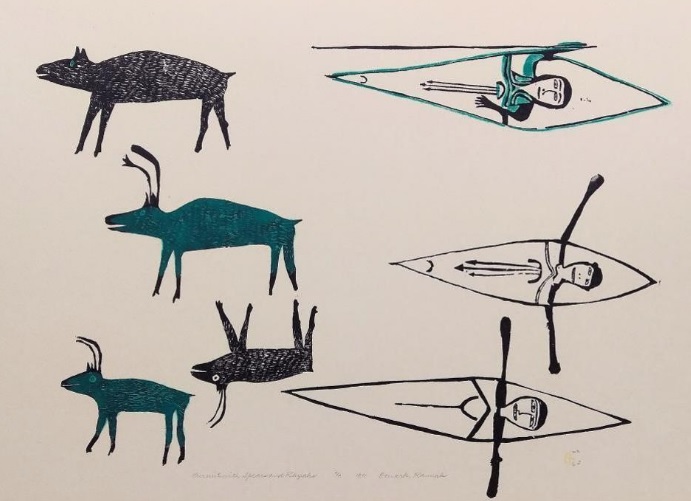

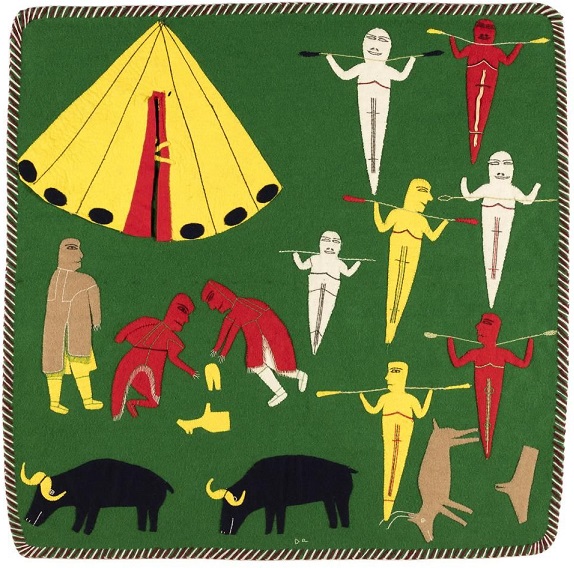

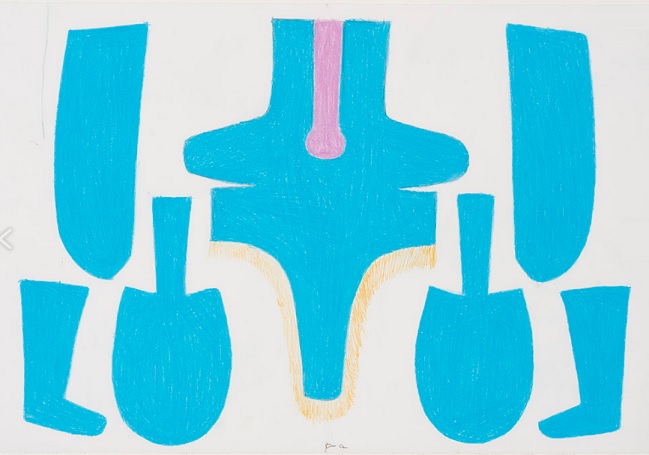

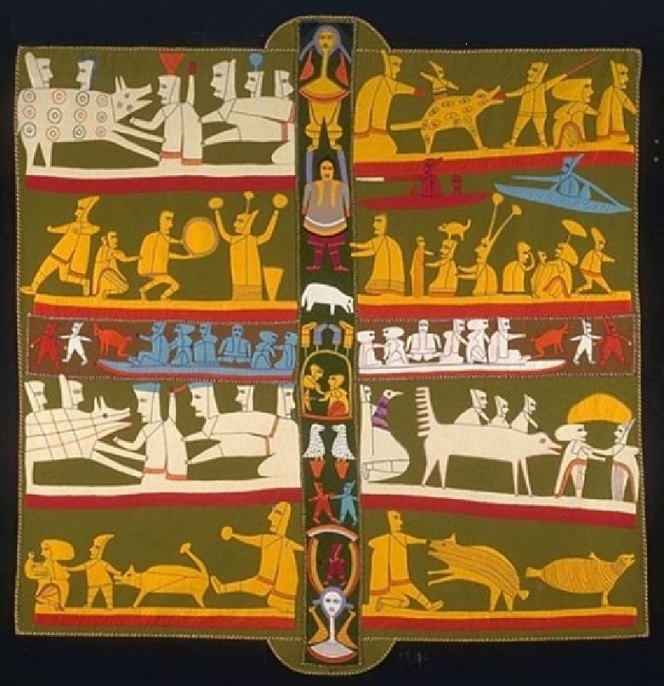

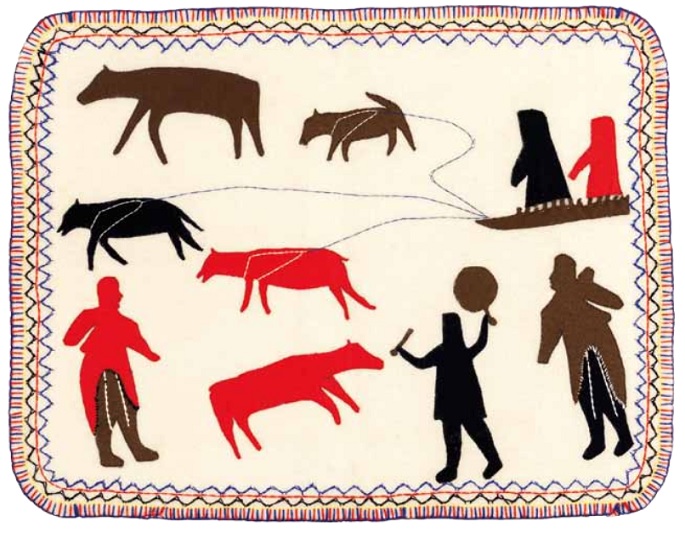

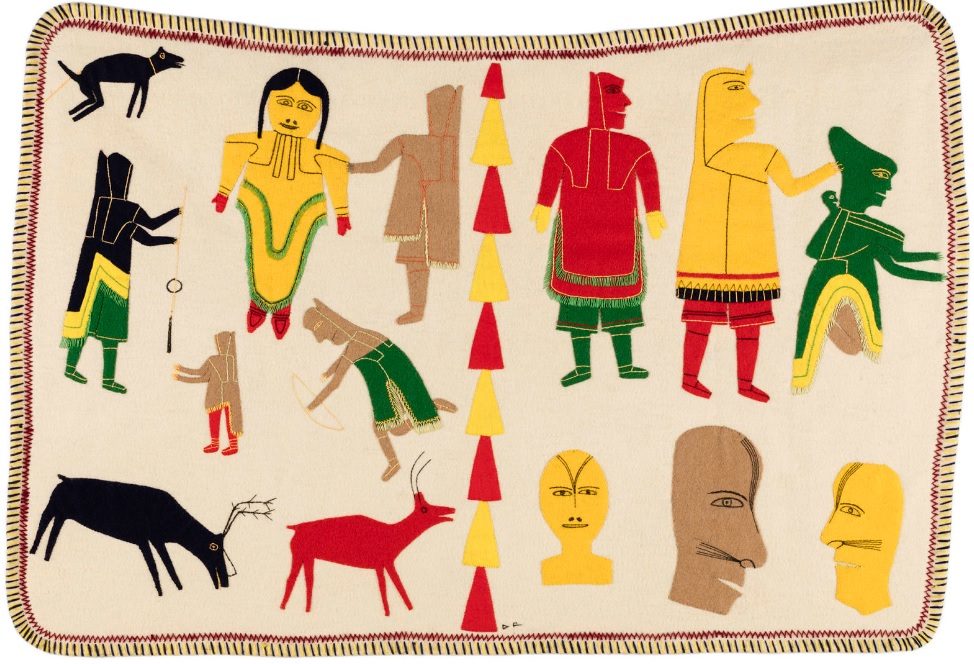

Her artwork portrays aspects of the traditional hunter-nomadic life that she lived for over five decades, moving from fishing the camp near the mouth of Back River on Chantrey Inlet in the Honoraru area to their caribou hunting camp in the Garry Lake area, living in winter snow houses (igloos) and caribou skin tents in the summer. Oonark learned early how to prepare skins and sew caribou skin clothing. They subsisted mainly on lake trout and Arctic char, whitefish, and barren-ground caribou. The knife used by women, the ulu, their traditional skin clothing, the kamik, the amauti were recurring themes in her work. Despite a late start – she was 54 years old when her work was first published – she was a very active and prolific artist over the next 19 years, creating a body of work that won considerable critical acclaim and made her one of Canada’s best known Inuit artists.” (Excerpts from Wikipedia – Note that there is much more written about Jessie’s life in the outstanding biography provided by Wikipedia.)

Jessie (Una) Oonark was born near the Haningayok (Back River), Nunavut and was named after her paternal grandfather, Una. Oonark lived the first fifty years of her life in Utkusiksalingmiut camps throughout the region. She pursued traditional tasks, such as processing and sewing caribou and sealskin to produce clothing. The aesthetic qualities of this work would later influence her depiction of Inuit life in drawings and tapestries.

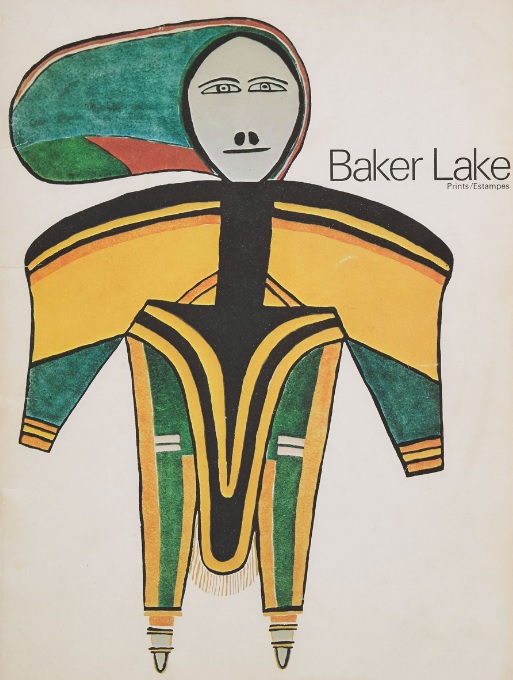

In the 1950s, Oonark and her family settled in Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake), NU, due to a decline in both caribou populations as well as the market for arctic fox furs. Oonark first began making drawings in the late 1950s. Her works quickly caught the attention of members of both the Qamani’tuaq and Kinngait (Cape Dorset) art communities. A few short years after beginning her drawing career, several of Oonark’s drawings were included in the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collections of 1960 and 1961, notable, as she did not reside in Kinngait.

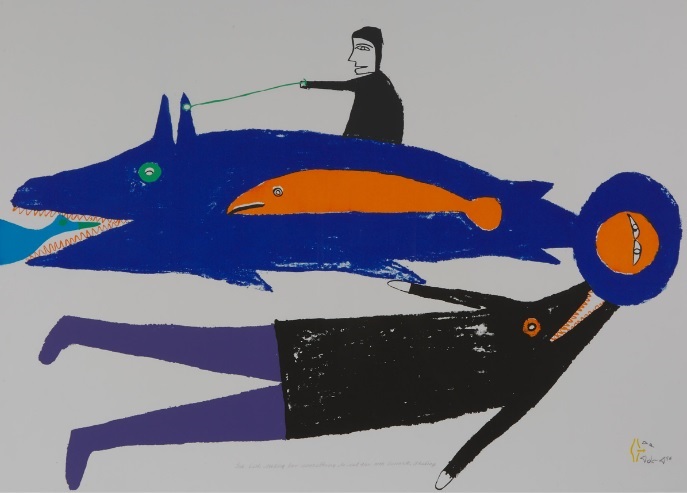

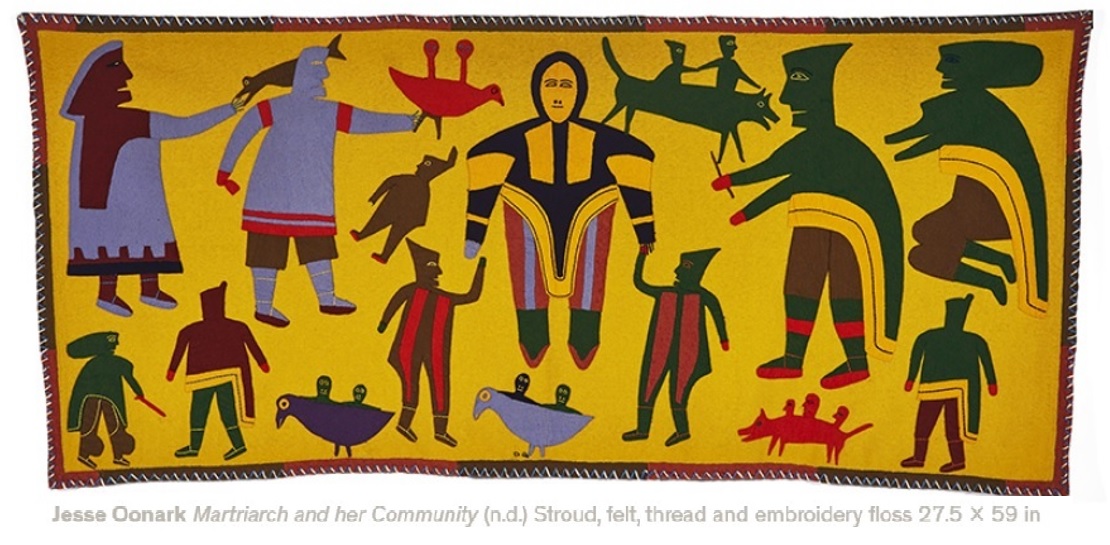

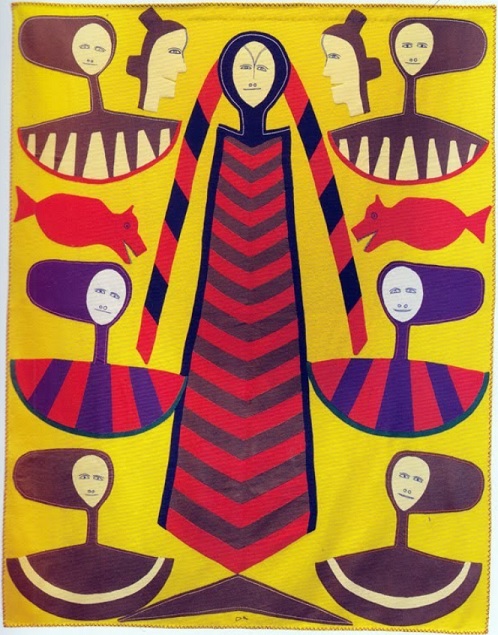

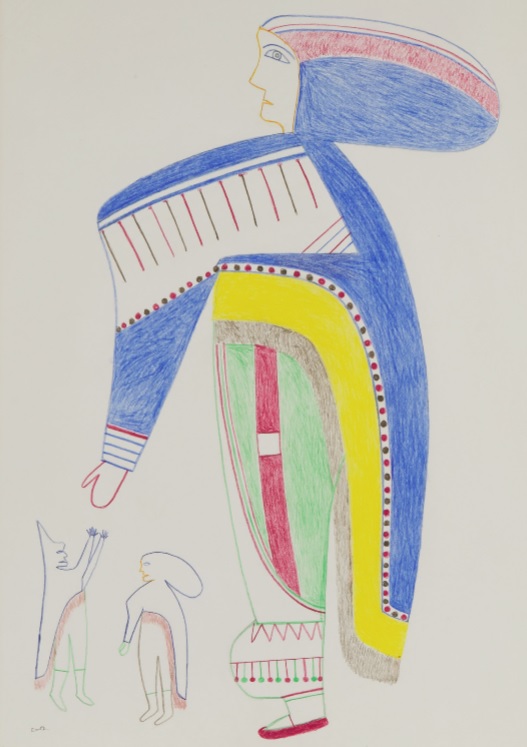

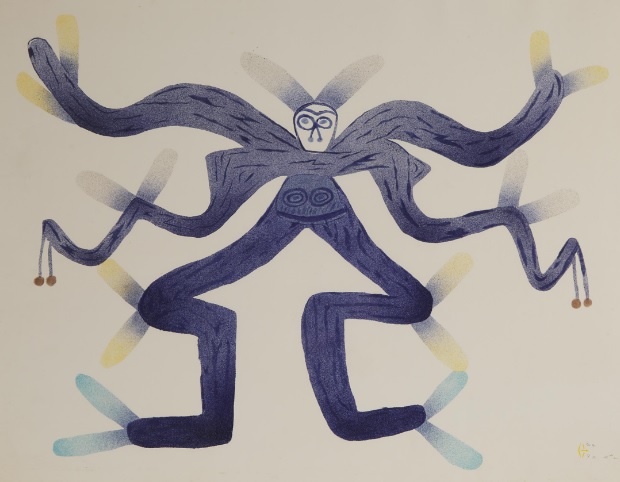

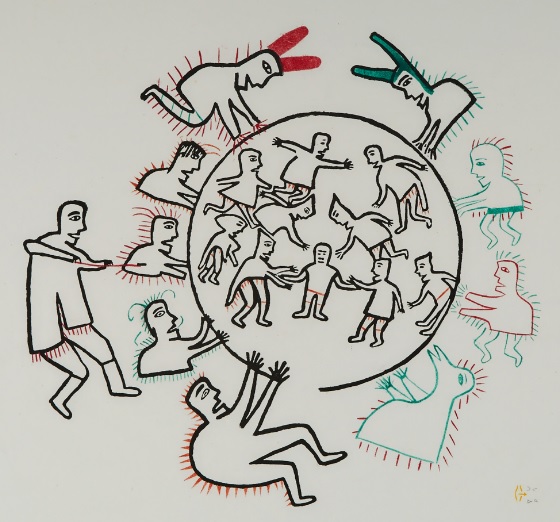

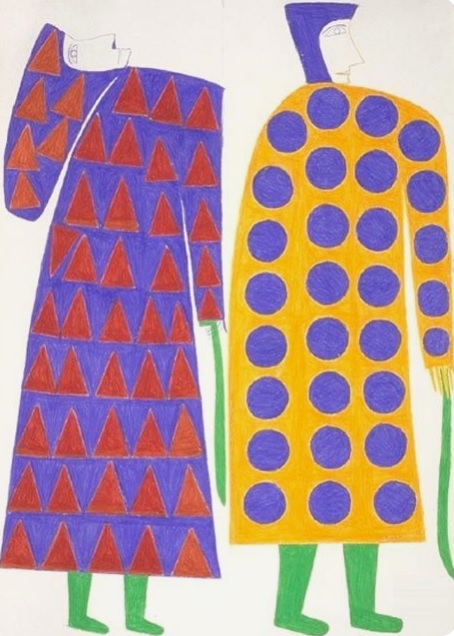

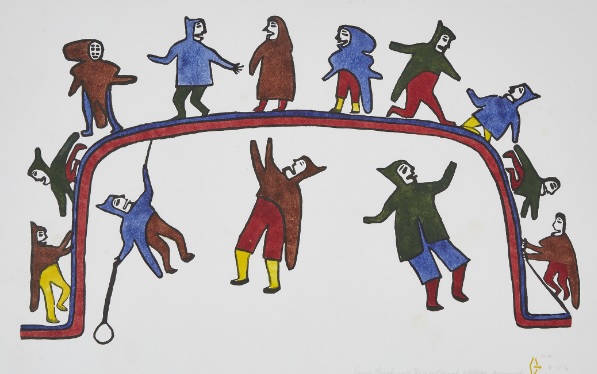

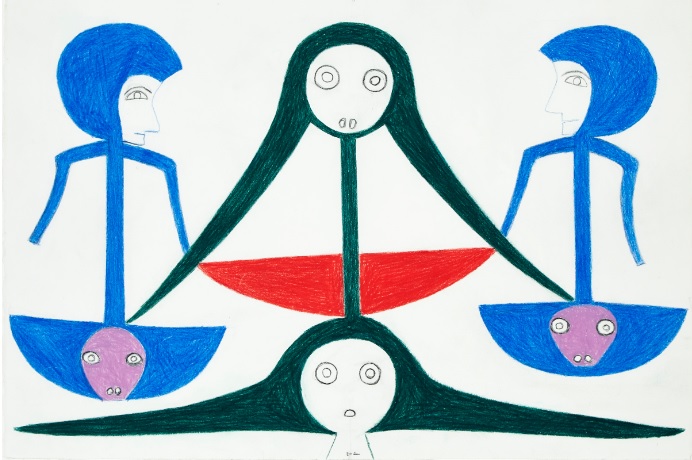

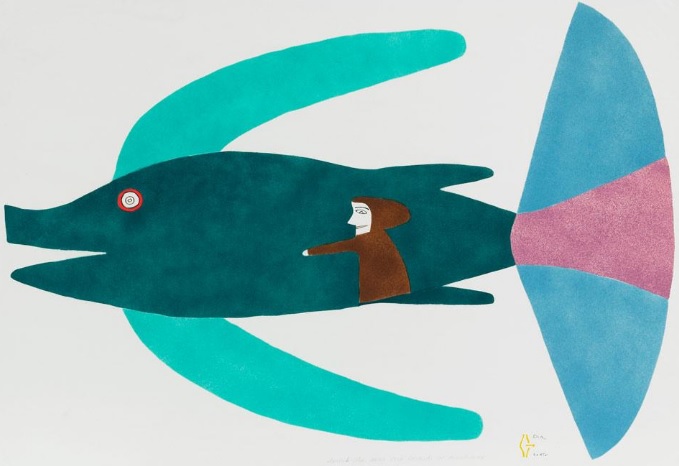

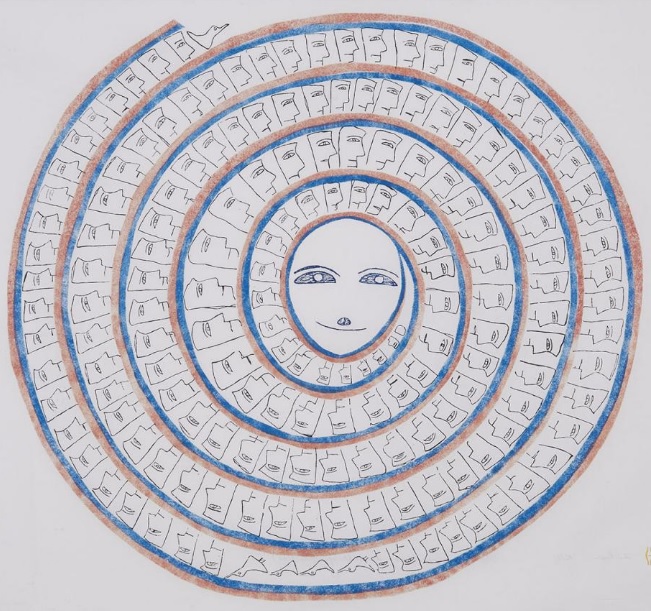

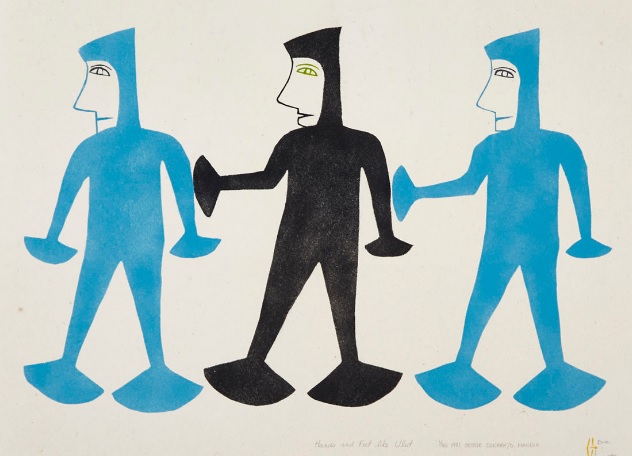

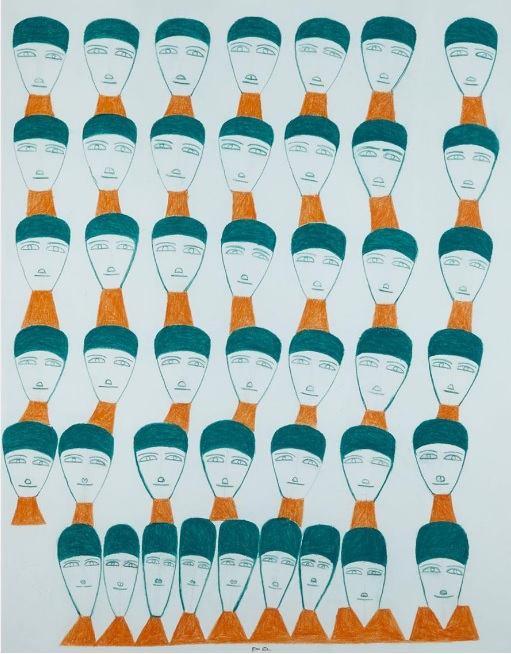

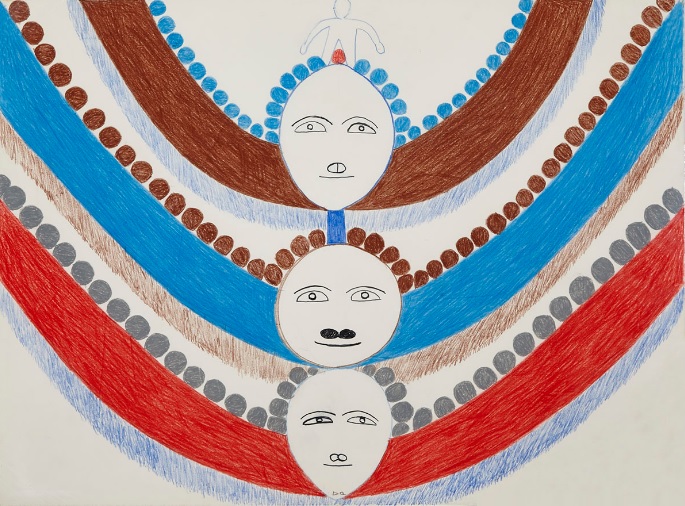

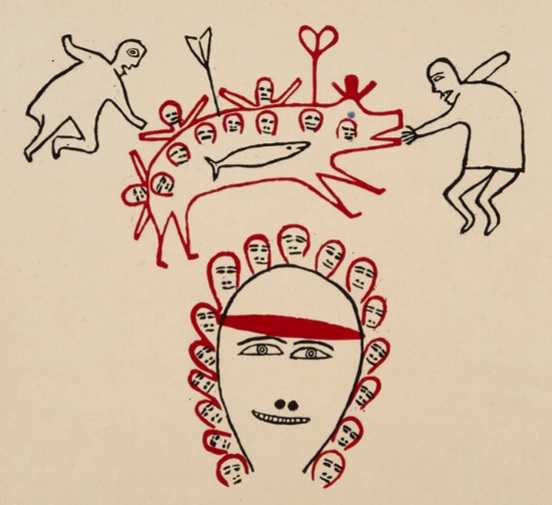

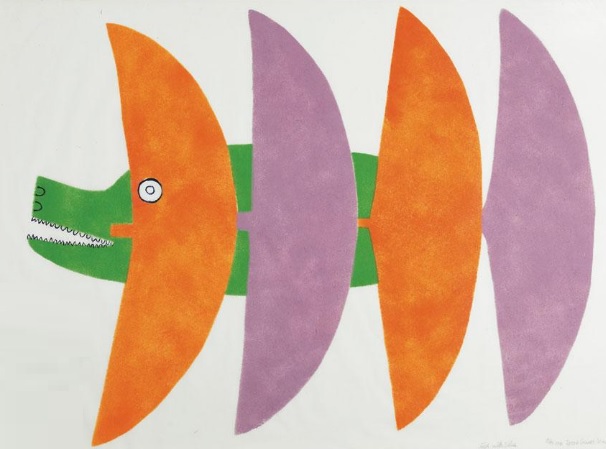

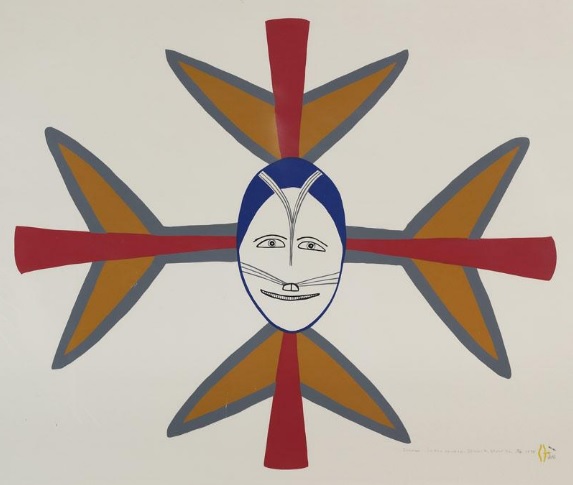

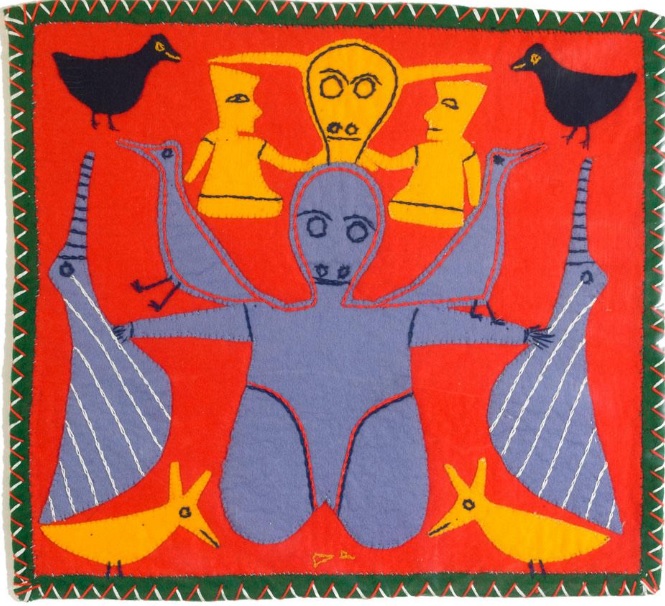

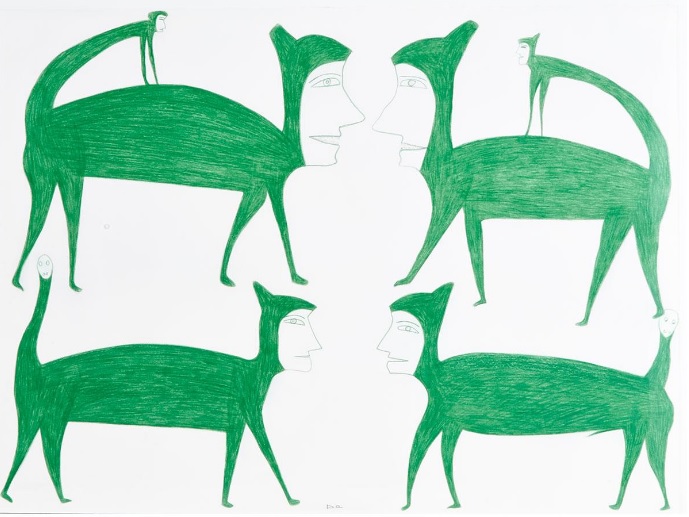

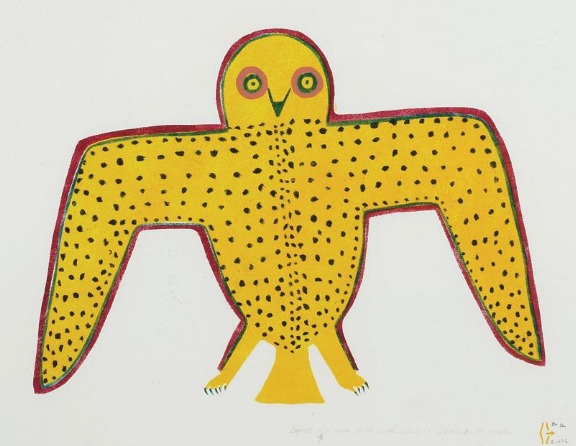

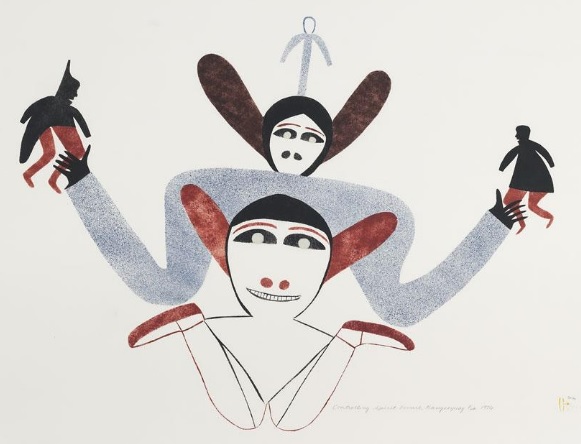

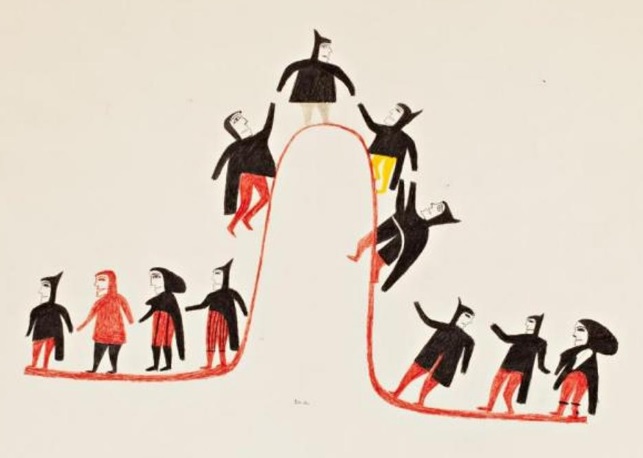

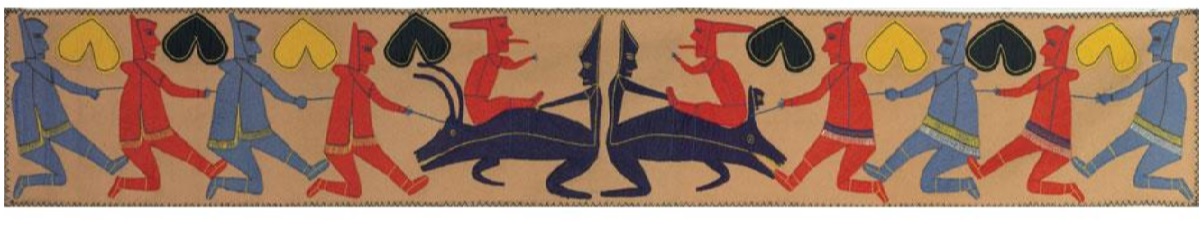

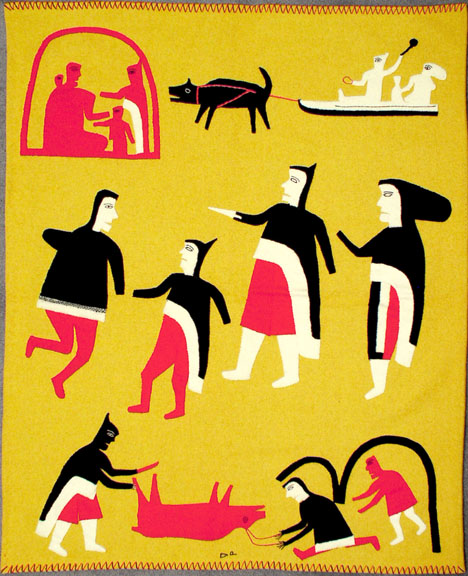

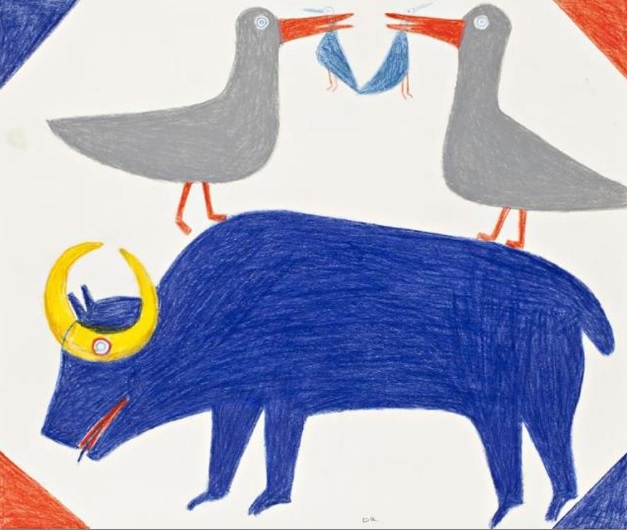

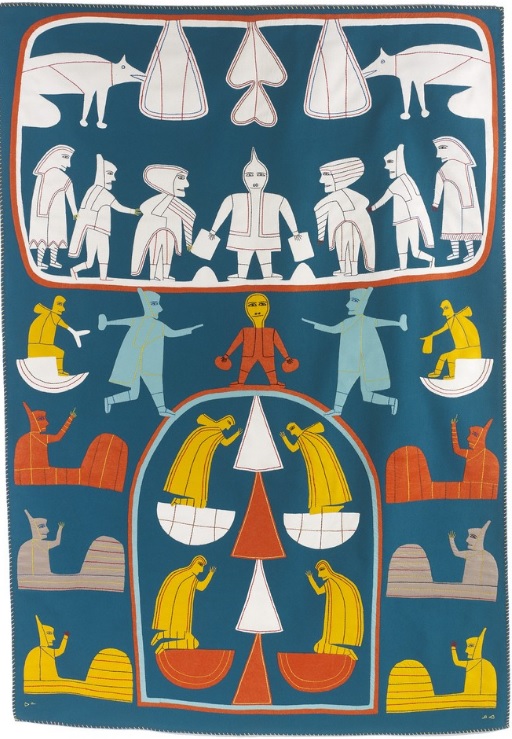

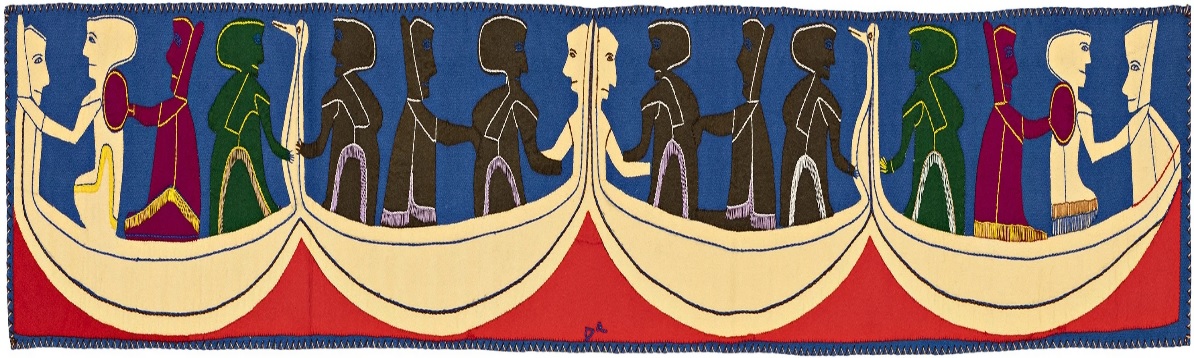

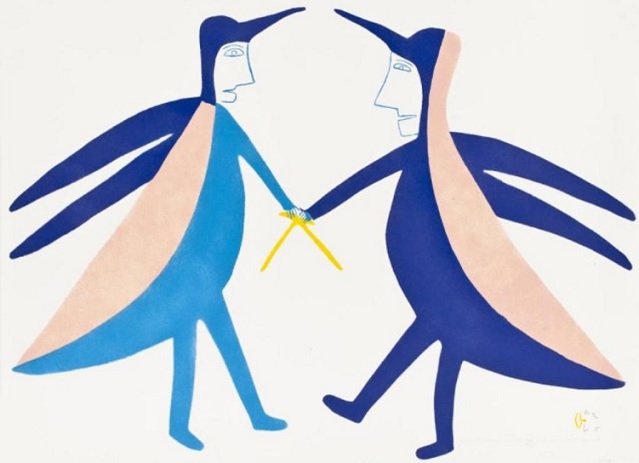

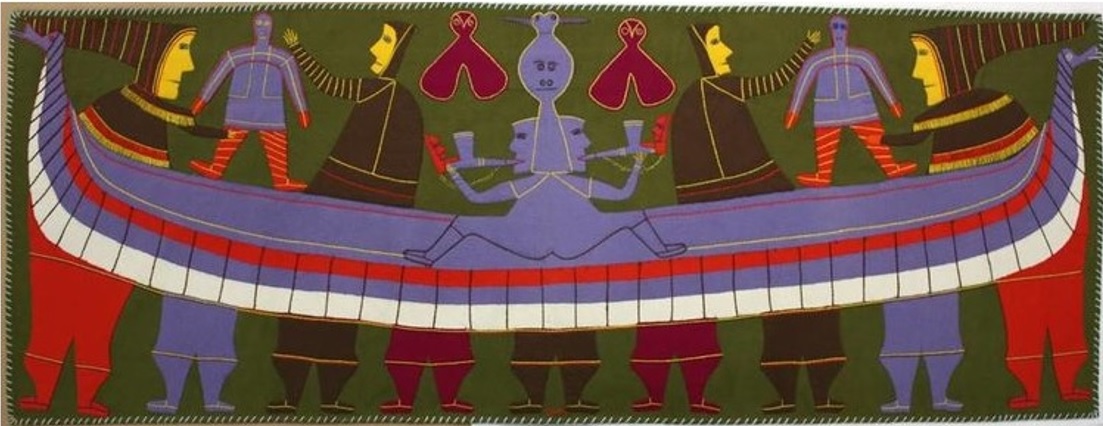

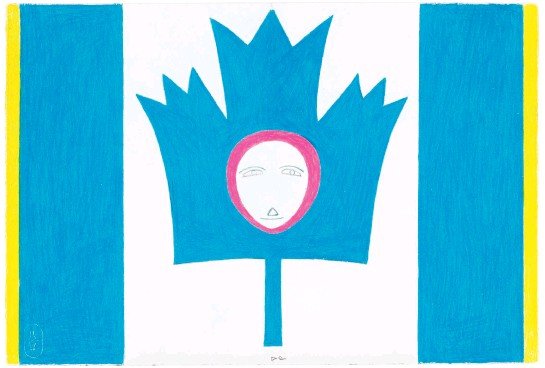

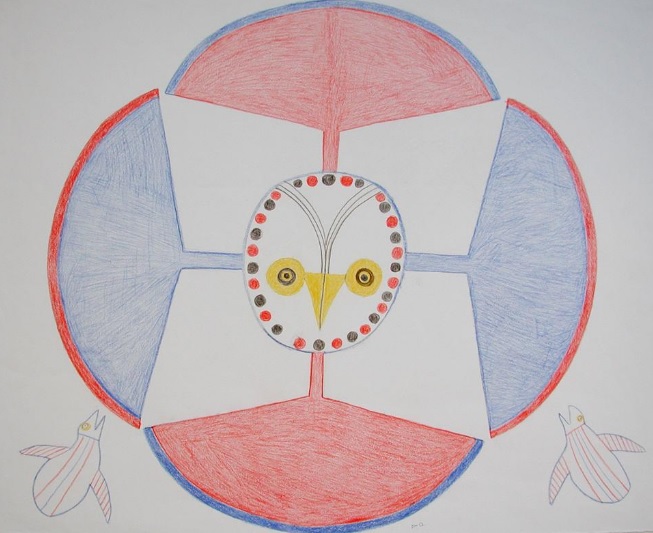

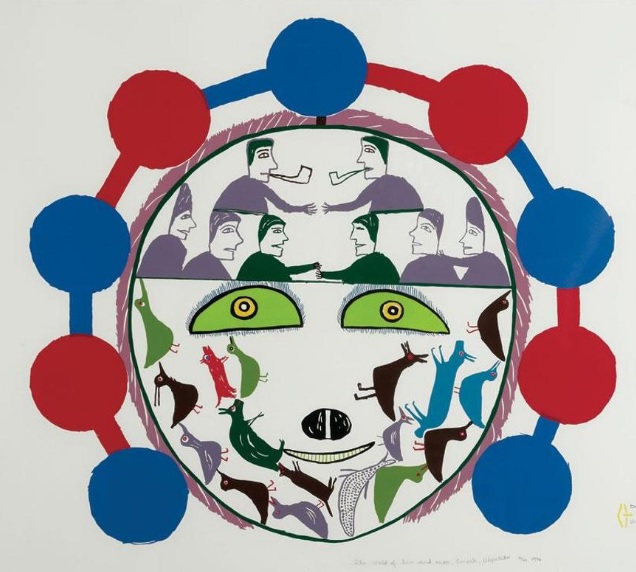

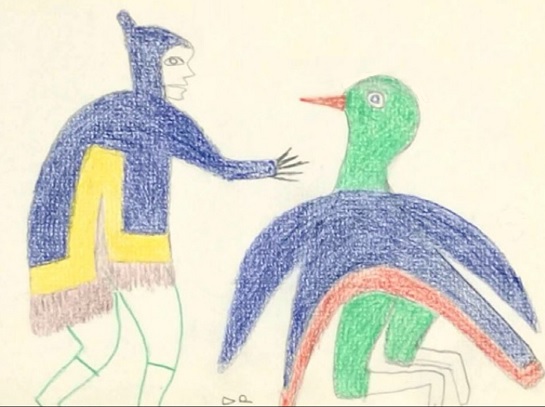

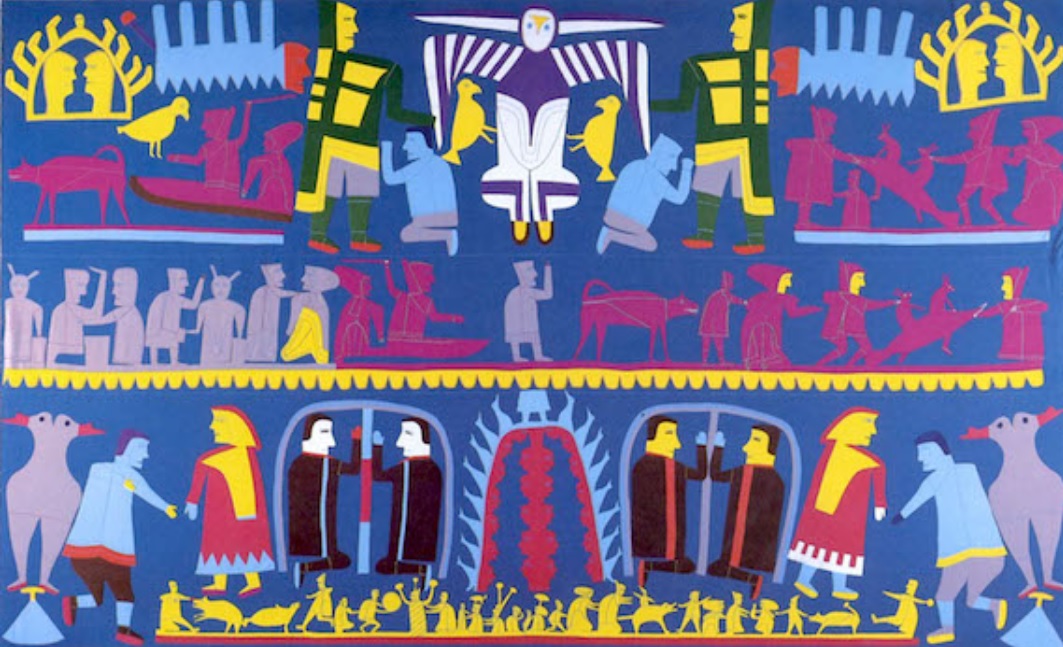

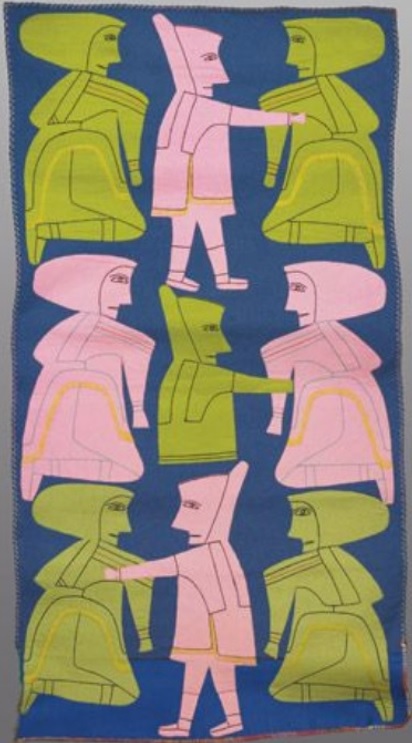

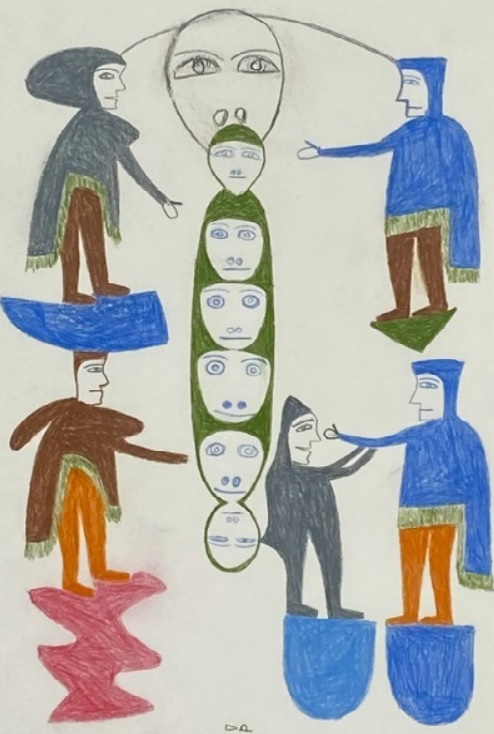

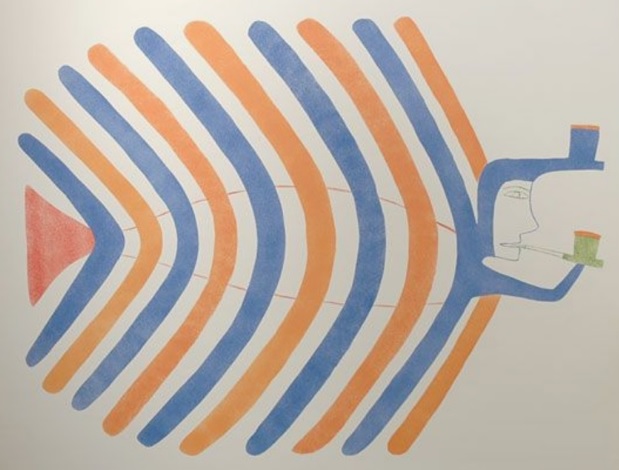

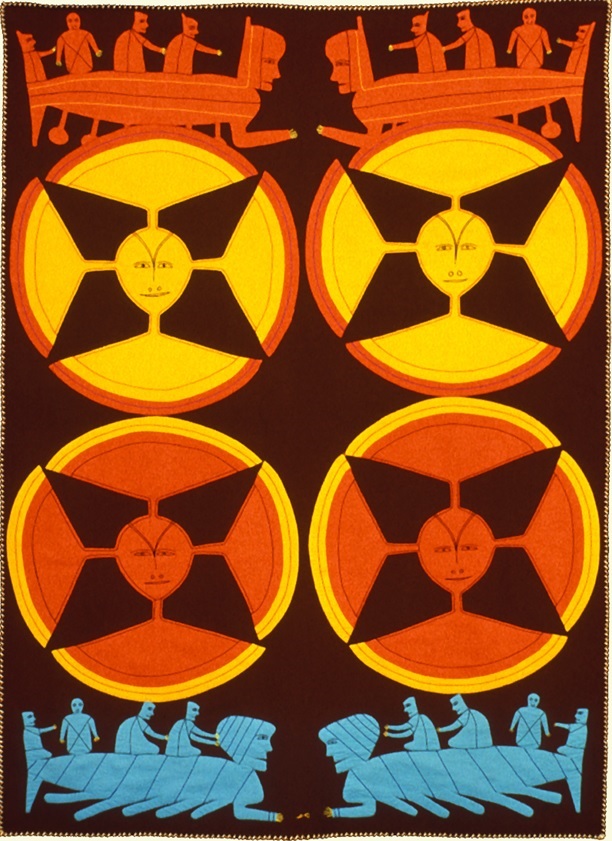

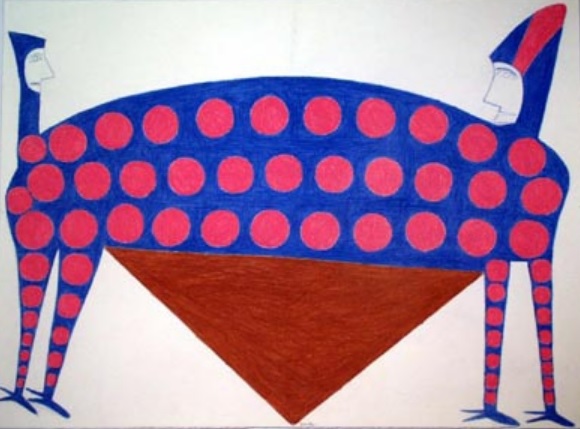

From her home, and eventually from a small studio in Qamani’tuaq, Oonark’s complex and vivid visual world unfolded. She employed bright colours in her depiction of humans, spirits and animals, creating vibrant works that draw the viewer in through pictorial storytelling. Often Oonark’s visual narratives focus on Inuit women, conveying their strength and power within traditional depictions of domestic activities. Discussing one of Oonark’s early drawings, Robert Enright describes “the whimsical, awkward gestures the figures make”, noting that, “the colours in the drawings speak unequivocally about Oonark’s uncompromising celebration of Inuit life”. An apt description of Oonark’s work, which can be applied to her oeuvre in general.

The central figure in her drawing Big Woman (1974) takes up the entirety of the page. The woman’s amautik is represented using striking colours and geometric patterns, complementing the design of her traditional facial tattoos. Two ulus protrude out of either side of her head and seated on top of her head is a second, relatively small figure. Oonark, who was once described as speaking very poetically, said that she depicted her dreams; the realities of Inuit life and the dreamlike world she imagined are both present in Big Woman.

In addition to drawing, Oonark produced wall hangings, one of which hangs in the National Arts Centre (NAC) in Ottawa, ON. The tapestry, commissioned by Bill and Jean Teron, was unveiled in May 1973; it hung in the foyer of the arts centre until 1994 when it was removed to be included in Oonark’s travelling retrospective. When it returned to the NAC, the tapestry was put in storage until 2013 when it was restored and re-hung for public display. Oonark was elected as a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1975 and was inducted as an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1984.

(Information provided by Inuit Art Foundation)